Five Steps Every Author Needs to Take Before Finishing a Manuscript

In 2016, after six years of writing, I finally finished my first manuscript. I truly believed that writing a book was the most difficult part of becoming an author. No one told me selling a book is tougher than writing one.

In 2016, after six years of writing, I finally finished my first manuscript. I truly believed that writing a book was the most difficult part of becoming an author. No one told me selling a book is tougher than writing one.

It is almost as if I believed, “If I write it, they will come.” Jane Austen didn’t use Instagram or Facebook or an author’s website. Harper Lee didn’t do podcasts much less interviews. Couldn’t I just be an introverted literary hermit and sell books? Unfortunately, not in today’s world.

Author Joanne Kraft said, “Not all marketing people are writers, but all writers must learn to be marketers.”

The average self-published manuscript only sells around 250 copies over the lifetime of the book. Even a traditionally published book only sells an average of 3,000 copies because publishers rely on the authors to do their own marketing. If you have written a book proposal, you know that the majority of that document describes how you, the author, will market your book.

That starts with understanding how to help readers find you and showing up in the world as the author you want to become. Before you even write that last perfect sentence, every writer needs to:

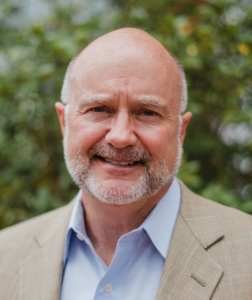

- Invest in an Author Headshot—study the back cover of books you like to read and create a similar professional photo that makes you look approachable to your potential readers.

- Write your Author Bio—create a summary of your professional qualifications or writing experience that let readers know why they can trust you as an author. Read author bios on your favorite genre and create in a similar style.

- Buy your author domain name—get your name registered so you can create a simple website where readers can learn more about you.

- Create an Author Landing page—sites such as Squarespace or Wix make it easy for you to use your domain name and have at least one page with your bio, headshot, and information about your writing or potential titles

- Create one author social media channel (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook) where you will begin engaging your potential readers. This should be separate from your personal accounts or turn your personal account into your author account to begin posting about subjects related to your genre.

With a professional-looking author presence, you will be ready for readers (and agents and publishers) to discover you even before your story is finished.

ABOUT KATHY: Kathy Izard is an award-winning author, speaker and changemaker. In the past five years, she has published four books three ways in two languages selling over 30,000 copies. Kathy believes we all have a story worth telling and loves helping writers find the courage to put their words in the world. Her new memoir The Last Ordinary Hour is available in paperback, Kindle and Audiobook. Learn more about Kathy: www.kathyizard.com

MASTER MARKETING WITH KATHY: Join Kathy for Marketing Your Book on December 6th, at 6pm (ET) online. Don’t wait until after your book is published to find your readers. Whether you are planning to self-publish or you already have a book contract, today’s authors need to know how to market their own books. More information here.

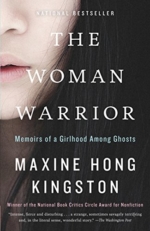

Two days ago, I finished reading The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts, Maxine Hong Kingston’s acclaimed 1976 memoir, and haven’t been able to stop thinking and writing about it since. In fact, I’ve already started re-reading in order to understand more fully why the book has so enchanted me, how the story of a woman born in America more than eighty years ago to Chinese immigrants has somehow connected me more deeply to my own story.

Two days ago, I finished reading The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts, Maxine Hong Kingston’s acclaimed 1976 memoir, and haven’t been able to stop thinking and writing about it since. In fact, I’ve already started re-reading in order to understand more fully why the book has so enchanted me, how the story of a woman born in America more than eighty years ago to Chinese immigrants has somehow connected me more deeply to my own story.