A Poet Responds to a Classic Painting

by Malin Pereira

Thrall, a 2012 collection of poems by Pulitzer Prize winner and 19th U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey, is replete with ekphrastic poems—those written in response to works of art. Of note are the poems focused on two painters: Diego Velázquez and Juan de Pareja.

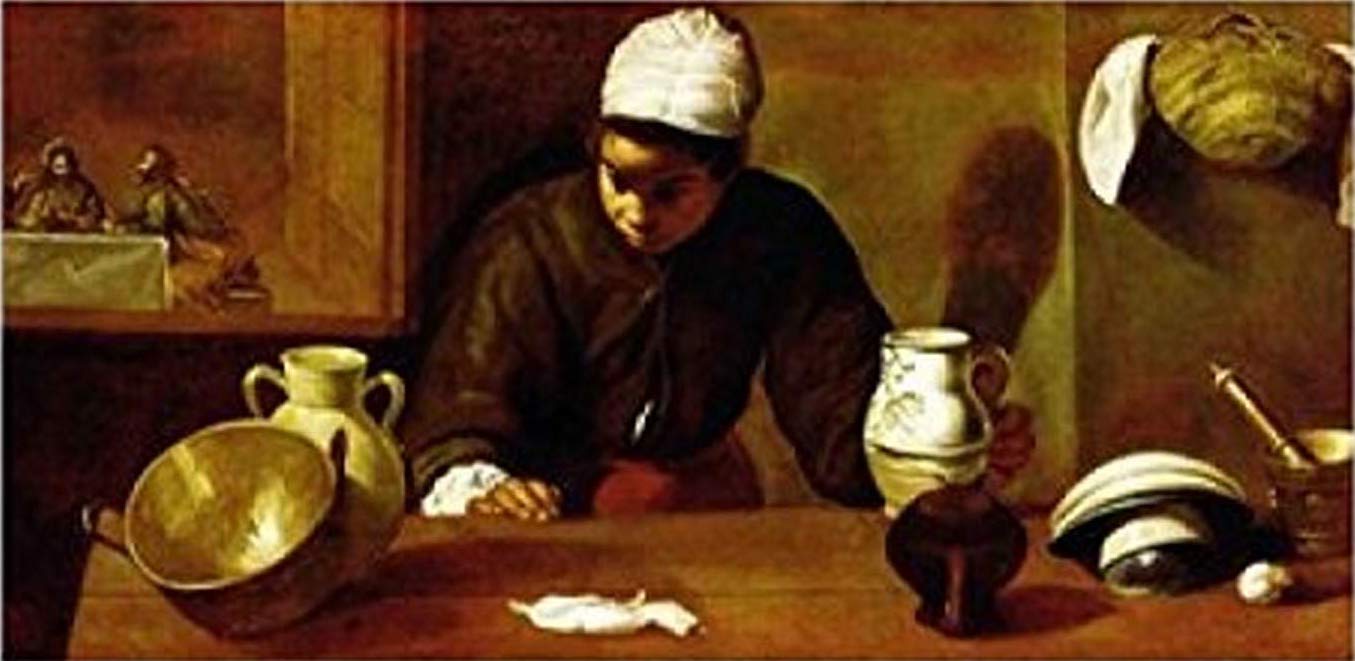

That Velázquez was a renowned Spanish Golden Age painter and Pareja his enslaved, mixed-race assistant suggests a power dynamic of multiple dimensions. Through an ekphrastic poem near the beginning of the volume on Velázquez’s “Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus” and another near the end on Pareja’s painting “The Calling of Saint Matthew,” Trethewey critiques Velázquez’s—and by extension, Western culture’s—representation of the black blood in mixed-race people as a “taint” diminishing their intellect and humanity. Her poem on Pareja, who was of both African and Spanish descent, offers a corrective narrative celebrating his talent and eventual freedom. Trethewey employs ekphrasis to make us see racism’s continuing grip on Western culture and black lives.

Velázquez, whether in the context of the Spanish Golden Age or the history of western painting, is a major figure. His “Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus” represents a scene in the Gospel of Luke in which Jesus appears to two disciples on the road to Emmaus. It is one of his “bodegón” paintings, a Spanish innovation—still-life paintings depicting kitchen scenes. In some, such as this one, Velázquez included a religious element.

Diego Velázquez, Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus, 1617-1618, oil on canvas, 55 x 118 cm. Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland.

Trethewey’s sonnet “Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus; or, The Mulata” appears in the first section of Thrall immediately following poems about the fractioning of blackness and blood in the Spanish castas system of racial classification. Her title gestures back to this theme of racial mixing through its hybridity, mixing the English and Spanish titles. The poem poses the “problem” of the mixed-race servant in the presence of the divine Jesus. Trethewey turns the sonnet’s traditional depiction of a lady’s beauty into a description of her racial mixing as depicted in Velázquez’s painting, which Trethewey critiques. The refrain “she is”—appearing five times—underlines the kitchen maid’s visual equivalence to the objects that surround her; she is a thing, a tool of the kitchen, just as they are, echoing plantation records in which slaves were listed alongside farm tools and household implements. Many of the items are specifically vessels—pot, pitcher, mortar, bowls, basket—all receptacles to be filled. The maid’s hand, represented as a tool that makes an imprint, is repeated four times to emphasize her function as a tool, a do-er.

Trethewey’s use of color imagery, specifically white, black, and a bit of red, foregrounds to us the racial classification logic of the painting, in which white functions not only as the part of her that’s racially white, but also represents what is pure and holy—the hint of Jesus in her. Blackness becomes a faint trace in the poem through its rhyme with “stack” and several “b” consonance sounds (bent, bowls, bulb, basket, bundled), which then becomes “blood.” The language “black one edged in red” conveys the racist stereotyping of blacks as sexually lascivious, as well as the taint of black “blood” in the mixed-race maid.

When I was at the Art Institute of Chicago recently, viewing another version of this painting through the prism of Trethewey’s words, I must say I could not “unsee” its racist dimensions. That’s powerful work done by one poem.

Learn about More About Natasha Threthewey’s Poems with Malin

THURSDAY, MARCH 21: “Ekphrasis, Lyricism and Race: A Study of Natasha Trethewey’s Thrall, 6:00–8:00 p.m. Charlotte Lit, 933 Louise Avenue (@hygge Belmont). Info and registration

In this class, we’ll discuss the themes in Thrall and look closely at the way the poems respond to paintings. Natasha Trethewey, a master formalist, is the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, including from the NEA and Guggenheim Foundation, and served two terms as the 19th Poet Laureate of the United States (2012-2014).

Malin Pereira, Professor of English and Dean of the Honors College at UNC Charlotte, earned her Ph.D. in English at University of Wisconsin-Madison, with a minor in Afro-American Studies. Following early work on Toni Morrison, her scholarship and teaching have focused on contemporary Black poetry. Her books include Rita Dove’s Cosmopolitanism and Into a Light Both Brilliant and Unseen: Conversations with Contemporary Black Poets. Her most recent publications are on Thylias Moss and Natasha Trethewey. Work in progress includes “A Black Cosmopolitan Poetics” for Cambridge University Press and “Contemporary Black Poets on Phillis Wheatley Peters.”