Origins of a Poem

by Chen Chen

This poem started out as a tweet that was a bit more lyrical than usual. One of my favorite joys: when poems come from unexpected, seemingly unpoetic places.

I Love You to the Moon &

not back, let’s not come back, let’s go by the speed of

queer zest & stay up

there & get ourselves a little

moon cottage (so pretty), then start a moon garden

with lots of moon veggies (so healthy), i mean

i was already moonlighting

as an online moonologist

most weekends, so this is the immensely

logical next step, are you

packing your bags yet, don’t forget your

sailor moon jean jacket, let’s wear

our sailor moon jean jackets while twirling in that lighter,

queerer moon gravity, let’s love each other

(so good) on the moon, let’s love

the moon

on the moon

Copyright 2021 by Chen Chen. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on May 31, 2021, then reprinted in Explodingly Yours (Ghost City Press, 2023). Reprinted with permission of author.

Learn to Write Poems Celebrating Connection and Love: A Masterclass with Chen Chen

TUESDAY, JANUARY 23: “Happy Poems!” 6:00-8:00 p.m. via Zoom.

Do happy poems exist? If they do, can they be as good as the poems that wreck us? Can a happy poem wreck us? And how can we avoid sentimentality or, is that a risk we just need to take? In this generative session, we’ll look at Ross Gay’s essay, “Joy Is Such a Human Madness” as a compass for our discussion and a starting point for writing about/from/through happiness, joy, and pleasure. Within the genre of happy poems, we’ll think about poems that celebrate love, sex, community, and connection of various kinds. Come prepared to engage in jubilant experimentation. Info and registration

About Chen

Chen Chen is the author of two books of poetry, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency (BOA Editions, 2022) and When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions, 2017), which was longlisted for the National Book Award and won the Thom Gunn Award. His work appears in many publications, including Poetry and three editions of The Best American Poetry. He was the 2018-22 Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence at Brandeis University and currently teaches for the low-residency M.F.A. programs at New England College and Stonecoast. Visit his website: chenchenwrites.com

Mindfulness & Poetry

by Brooke Lehmann

In my meditation circle a few weeks ago, our group leader asked us to name one of our wisdom teachers. The contemporary poet and Zen Buddhist Jane Hirshfield came to mind; I was currently reading her new collection, The Asking. Hirshfield’s poems are filled with ordinary acts such as picking figs or opening a window. Many of her poems grapple with difficult questions: the climate crisis, aging, and human suffering. They often instill a sense of wonder and gratitude alongside grief and loss.

In my meditation circle a few weeks ago, our group leader asked us to name one of our wisdom teachers. The contemporary poet and Zen Buddhist Jane Hirshfield came to mind; I was currently reading her new collection, The Asking. Hirshfield’s poems are filled with ordinary acts such as picking figs or opening a window. Many of her poems grapple with difficult questions: the climate crisis, aging, and human suffering. They often instill a sense of wonder and gratitude alongside grief and loss.

In the early days of reading poetry, I was drawn to the imagery and music of the language. But over the years, I have realized that the poems I love the most are not just filled with writing craft, but they also teach me the most about how to live well or more mindfully. Hirshfield says, “Through poetry I know something new, and I have been changed.”

Mindfulness is living in the present moment, accepting our thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations without judgment. Mindfulness is a quality everyone possesses, but we must learn how to access it. Like any new routine or habit, the more we practice, the easier it becomes over time. We can exercise mindfulness in everyday activities like walking, cooking, folding laundry, or reading a poem.

Research suggests a regular mindfulness practice reduces stress, improves mood and focus, strengthens our immune system, and stimulates learning and creativity. Mindfulness can also help us have happier relationships, make us more resilient to suffering, and allow us to cultivate compassion for ourselves and others. Similar to practicing yoga, we can feel kinder towards ourselves and others by reading mindfully.

We see poets like Craig Arnold, with his poem, “Meditation on a Grapefruit,” slow his readers down to the simple act of savoring a piece of fruit over breakfast before the day’s stressors set in. In the poem “Thank You” by Ross Gay, readers are placed barefoot on the frosty grass of a dormant garden in early fall. Through enlivening the senses, we are gifted with greater clarity in the present time. It’s one thing to be on a meditation retreat away from distractions, but by reading, we can learn to witness mindfulness in moments of daily living.

As we live in increasing uncertainty in our ever-changing world, I routinely turn to poetry to ground me in the present moment. Against the terror and dread that we face with gun violence or threats of war, reading mindfully helps me see the beauty alongside the pain in others’ experiences. It reminds me of possibilities that exist in what I often tend to overlook. Right now, the invitation to open to the dark drop of autumn and watch nature surrender to its own wisdom.

About Brooke: Brooke Lehmann is a poet and creative who draws inspiration from nature, fashion, and her love of the piano. Her poems have been featured in Tar River Poetry, Pedestal Magazine and others. She was longlisted for the 2022 Palette Poetry Sappho Prize for Women Poets, and her chapbook manuscript, Pillar of Exquisite Sorrows, was named a finalist in Tusculum Review’s 2023 Chapbook Prize. Brooke holds a B.S. from Purdue University and is a graduate of the Arts and Science Council Cultural Leadership Training program. She serves as an advisory group member of Charlotte Center for Mindfulness.

Practice Mindfulness with Brooke: “The Poetry of Presence: Reading as a Path to Mindfulness,” Thursday, November 9, 2023, 6:00-8:00 p.m., virtual via Zoom.

In this class we’ll explore a few poems and short pieces around the theme of mindfulness. Class will open with a guided body scan meditation followed by a series of readings that follow the style of lectio divina or dharma contemplations. We’ll respond to how the essence of the poems take shape in an embodied way as we hear them recited, informing our emotional and inner landscapes. As a group we’ll discuss images or phrases that catch our attention, and the way metaphor creates meaning and resonance in our lives. We will also have time for a mindful writing exercise and optional sharing. Info

Celebrate the Writer You Are AND the Writer You Can Become

By Ashley Memory

While no one likes to get a rejection email, I recently received one that wasn’t quite as bad as most. It read: “Unfortunately, your submission is not the right fit for what we’re seeking at the moment, but please know that your story is valid and important. We would love to see your work again Ashley!”

I realize that this message was a form letter, and even the name field was auto-populated, but it had a curious effect on me. This note not only softened the blow, it also made me feel better about my writing. It reinforced my belief that all writers instinctually pull from a collective consciousness of love, sadness, grief, joy, and everything in between. This does indeed make my work, and your work, both valid and important.

From one writer to another, I urge you to take this opportunity to love yourself and your work. As often as writing exhilarates, liberates, and soothes, it equally infuriates, bewilders and exhausts us. That’s why it’s so important to give yourself permission to write and believe in your work.

To help, I’ve provided six quick steps designed to celebrate both the writer you are and the writer you can become.

1) Remember the time when you first knew that you were a writer. This happened for me in the sixth grade, when I wrote a poem on the first Thanksgiving that my teacher Mrs. Robbins posted outside the classroom. My first “masterpiece” was a little corny, and certainly contained predictable rhymes, but it meant so much that a teacher I admired was proud of me. I want to do this for the rest of my life, I remember thinking. This little victory has sustained and lifted me up ever since.

2) Tell people that you’re a writer. This step is so obvious I almost didn’t include it. But in my career, I’ve met so many people (even at writers’ conferences!) who hesitate to call themselves writers. They scribble under the cover of darkness, never share their work, and don’t trust themselves enough to tell the world about their greatest, albeit secret, passion. It’s time to come clean. “Outing” yourself as a writer will bolster your confidence and open a new world of friends and connections.

3) Celebrate your strengths. Marilyn, a dear writing partner, recently asked me to compile a list of her greatest writing strengths, something that I was delighted to do. She plans to use this list as part of her 2023 writing plan, which in my mind is nothing short of brilliant. You should do the same. Ask someone in your life—either a fellow writer or a reader of your work—what they admire most about your writing. Keep this list handy and refer to it often.

4) Love your writing enough to make it better. While it’s important to celebrate our talents and victories, it’s vital that we look beyond those moments and seek to improve. If you’re naturally good at setting a scene, consider pushing yourself to add more conflict. If characterization is your strong suit, tinker with your descriptions a little more. Or get better at finding just the right word to express yourself. One of my Christmas presents was the game “Wordsmithery” and by playing it, I hope my writing will soon be much more incandescent.

5) Post self-affirmations where you can see them. I’m living my best writing life. I move people with words. I will write a new poem every week. I will achieve my writing goals this year. You can post these by your writing desk or on your computer screen, but you can also stick them up throughout your home. Because we writers know that some of our best writing happens in our head—when we’re not actively writing. For example, I like to post my notes over the cooktop, on my nightstand, and even in the mirror. Collect your own affirmations, read them out loud, and repeat often.

6) Challenge yourself by submitting to a more competitive market. What is your dream publication? Have you been putting off submitting out of fear? Doubt? Procrastination? Don’t automatically assume that you’ll get a “no.” Just the act of considering ourselves worthy of our most aspirational markets is an elixir to the psyche. Start submitting to more selective markets and I promise that you will begin to see yourself and your work in a new light.

And on this note, why not start NOW? That’s right. Step out of your comfort zone and submit your work to an editor who might be waiting just to hear from you.

Piece by Piece

by Jaime Pollard-Smith

“Because in real life, unlike in history books, stories come to us not in their entirety but in bits and pieces, broken segments and partial echoes, a full sentence here, a fragment there, a clue hidden in between. In life, unlike in books, we have to weave our stories out of threads as fine as the gossamer veins that run through a butterfly wing.” ~Elif Shafak, The Island of Missing Trees

Kintsugi is the centuries-old Japanese art of fixing broken pottery. The word beautifully translates to “golden joinery.” This process involves piecing together fragments of broken pottery and filling in the cracks with gold. The shimmering seams not only add value, but they create a one of a kind piece that cannot be replicated. Brokenness builds beauty. I like to apply this same process when writing creative nonfiction.

My writing students often struggle with knowing where to begin. How far back do they need to travel to enter the story? They feel a burden to provide all of the context up front. We are conditioned to produce “Once upon a time…” and “Happily ever after…” stories; yet that is never how our minds actually construct meaning. Readers might crave chronology, but it does not represent our internal life. Our life itself is an act of “golden joinery,” which is why I propose my students dive right into the messy middle. They can pick any moment from their life that they remember vividly. William Zinsser encourages writers to think small. If they have held onto a memory, it is there for a reason. Writers such as Anne Lamott teach that we don’t have to know what we are doing in order to just start the process of writing. Writers might not even know a beginning until they figure out where they are going.

Once the writer feels the freedom to write in fragmented pieces, the possibilities are endless. It becomes a process of discovery rather than production. I tell my students to write in vivid detail, capture the feeling and paint the picture. Show us the sweater, the sunset, the creaky staircase, the broken crayons, the hole in the sock, or the tear stained cheek. Zoom in again and again like exploring different pinned spots on a map. Reel us in, then step out and re-enter a new time and place. These snapshots can be joined in a beautiful new arrangement somewhere down the road. Don’t worry yourself with those details at the start. Enjoy the unfolding as you pick up the pieces.

Explore writing piece by piece with Jaime Pollard-Smith and Zeba Mehdi: “Framing Our Experience: A Life in Pieces” at Charlotte Lit, Tuesday, September 12, 6:00-8:00 p.m. Info

Jaime Pollard-Smith is a full-time writing instructor at Central Piedmont Community College with a Master of Arts from New York University. When she is not corralling two teenagers and a doodle named Dexter, she can be found practicing yoga, weightlifting, hiking, journaling and enjoying the arts. Her fiction has been published in Literary Mama, and she is a contributor for Scary Mommy and Project We Forget. Online: unbecoming.co.

Networking for the Introverted Writer

by Sarah Archer

Some of my earliest memories are from preschool, where there was an old cast iron tub, with rubber ducks painted on the sides, sitting in the middle of the room. The tub was filled with stuffed animals—and books. While the other kids ran around me and played, I just wanted to sit in that tub and read.

Growing up, I was always the girl with her nose in a book. The life of a writer seemed perfect, because not only did I love to read and write, I enjoyed living inside my own head. When I went to Los Angeles to pursue screenwriting, I faced an abrupt awakening. It turns out screenwriting is a very social career. The adage that it’s all about who you know is true. Screenwriters work collaboratively, take frequent meetings, and pitch themselves at every opportunity. I later learned that publishing is similarly social, albeit in different ways. Authors have more solitude during the initial writing process, but are responsible for the lion’s share of promotion. Engaging over social media, giving readings and interviews, and utilizing beta readers are all key.

My kneejerk reaction to all this was “Excuse me? I did not become a writer to talk to people. I became a writer to sit alone in a turret and gaze out the window.” I considered being like Emily Dickinson: hiding all my work in my bedroom, then posthumously becoming one of the most lauded writers of all time. But I had to concede that there is, after all, only one Emily Dickinson.

So I did what I saw other screenwriters doing: I networked. I did drinks with anyone I could in the industry. I attended mixers and workshops for aspiring writers. I joined critique groups. I kept in touch with people I had met, offering to read their work or help in any way I could. Later, when I wrote and published my first novel, I joined writing groups hosted by bookstores and libraries, and discovered the rich community of book lovers on Instagram.

All of these efforts have taken time, and, particularly for an introvert, the social aspects have required energy. But over the years, building a community of writers and readers has become one of the most rewarding parts of my writing life. I’ve learned about the entertainment and publishing industries, gotten invaluable feedback, sold books and scripts, and been hired for writing and teaching jobs. I’ve also found many of my best friends within the writing world. I even met my husband at a networking event.

Building a community and marketing yourself can seem daunting, but there are so many ways to personalize the tasks to your own strengths. I’ve also found writing communities to be incredibly welcoming. Even if you’re an introvert, as a writer, you can and should network! At heart, I am still—and always will be—that girl with her nose in a book. If I can find career and personal fulfillment through networking, anyone can.

About Sarah

Sarah Archer‘s debut novel, The Plus One, was published by Putnam in the US and received a starred review from Booklist. It has also been published in the UK, Germany, and Japan, and is currently in development for television. As a screenwriter, she has developed material for MTV Entertainment, Snapchat, and Comedy Central. Her short stories and poetry have been published in numerous literary magazines, and she has spoken and taught writing to groups in several states and countries. She is also a co-host of the award-winning Charlotte Readers Podcast. Online: at saraharcherwrites.com.

Learn the Networking Ropes with Sarah…and Bring a Friend!

Wednesday, September 6: “Building a Community: Networking for Writers” with Sarah Archer, 6:00-8:00 p.m. at Charlotte Lit.

This Class is a “Plus One” — Bring a Friend for Free! In honor of Sarah Archer’s novel, The Plus One — and because some things are easier with a trusted companion — you can bring a “plus one” to this class at no extra cost! Info

The Healing Potential of Writing

by Elizabeth Hanly

Once upon a time, a student told me his story. He told it in the voice of a child, since he was still quite young when the story occurred. The student had been kidnapped in Guatemala. His captors complained about his tears. “My mother complained of my tears too,” the student wrote. “Maybe that is way she let these men take me.” With that, suddenly, the student understood what he had been unconsciously carrying around with him for over a decade. And with that, I became super curious about the healing potential of writing.

I discovered a mountain of research that suggests writing uses neural processes that function beneath the level of awareness. When those processes are given rein through writing, “stuck” internal narratives can be challenged, freeing intuitive insights to come into awareness. Translation: Reflective writing is a way to discover insights you didn’t know you had.

And so when asked to work with the prompt “Memory that won’t let you go,” a cancer patient found herself writing of the prayer shawl her dad wrapped her in on Saturday mornings before he set off for synagogue. Quite an image to take with her into chemo. Another patient found herself remembering the carved wooden box her father had continued to work on for her even during a decade of the most heated and bitter of exchanges. These stories came to their writers unbidden. The writers couldn’t have known beforehand how healing these images would become. I watched in wonder.

I’ve watched in wonder as well at the laughter shared among the folks in my groups.

Friends sometimes ask me why this work? Because the space shared in these workshops is—dare I say it?—holy. Yep. That’s why.

Write with Elizabeth Hanly. “Togetherness: Writing for Those Touched by Cancer and Other Serious Illness” meets four Tuesdays beginning July 18, via Zoom, 6:00-8:00 p.m. Register

Elizabeth Hanly is a widely published freelance writer, covering the arts, refugees and issues of faith and healing. Her reporting has led her all over Latin and Central America, as well as the Caribbean. Her work appears in the New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, Vogue, and others. She is an affiliate professor at Florida International University’s (FIU) Herbert Wertheim’s College of Medicine and leads writing workshops for patients at NYC’s Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Cancer Center. Online: www.elizabethhanly.com.

The Challenge is the Gift

By Beth Murray

Irania Macias Reymann and I are collaborators, kindred creative spirits, and we’ve written two plays together.

In 2013, we wrote and toured a bilingual show with music for children called Mamá Goose. It was inspired by the beautiful Latino nursery rhyme anthology of the same title by Isabel Campoy and Alma Flor Ada. In that project we challenged ourselves to make a play engaging and relevant to young audience members across language and cultural borders. We used music, movement, English, Spanish, American Sign language, playful actors, and all the design elements of theatre to tell the story for a diverse audience.

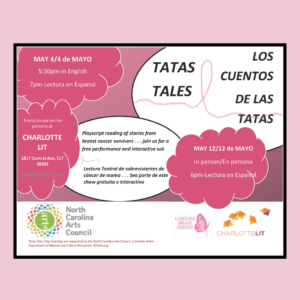

Our second play, Tatas Tales: Los Cuentos de las Tatas, is also an adaptation of sorts. We created the play based on the writing, conversations, drawings, stories, and community of breast cancer survivors participating in Irania’s bibliotherapy groups—some Spanish-speaking, some English-speaking. At this moment, we have an English and a Spanish version of the same play written to a point where actors can read the piece for an audience, and seek a response.

Despite the vast age and topic differences, both projects bear similarities. Both involve navigating cultural and linguistic borderlands with story. Both projects involve adapting existing material that is not in a single-narrative form. Both projects began with one of us saying something like: “There’s this thing. It has possibilities to be a play. I have no idea how right now. Will you collaborate with me?” We always say “Sí.” And then we see.

The challenges are the gifts. The weaknesses are the strengths. The doubts are the possibilities. The community matters more than we do. So, yeah. It takes us a long time to create a play. The plays become of a place and of the people who shape them along the way. For Tatas Tales, there have been many people and places.

Program administrators who held space for creative breast cancer therapies.

Bold and brave writing group members.

Readers and performers of early drafts on Zoom.

Community programmers and librarians willing to open their doors to our reading events. Media folks.

Current cast members.

Irania and I are named as playwrights, but Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas reflects a plurality of authors, as the story is continually written and re-written in rehearsal and performance choices by the ensemble, even as the words stay constant. Our current cast includes five actors.

Irania and I are named as playwrights, but Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas reflects a plurality of authors, as the story is continually written and re-written in rehearsal and performance choices by the ensemble, even as the words stay constant. Our current cast includes five actors.

The photo shows 12 people (a 13th in spirit). Among those smiling faces are professional performers, novice performers, breast cancer survivors, witnesses to breast cancer, monolingual English speakers, emergent Spanish speakers, bilingual speakers with varying degrees of comfort and confidence with English and Spanish, fluent multilingual speakers, young professionals, middle-career professionals, and retirees. This patchwork of people will bring the script to life. The initial challenge of not having five bilingual actors available for all performance gave way to this richness.

The challenge, again, became the gift. It is a generous one.

JOIN US for Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas:

JOIN US for Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas:

Wednesday, May 4: In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two, 5:30 p.m. in English – Register

Wednesday, May 4: In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two, 7:00 p.m. in Spanish – Registro

Thursday, May 12: Hybrid event, 6:00 p.m. in Spanish

• In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two – Registro

• Virtual through Charlotte Mecklenburg Library – Registro

NOTE: Proof of full Covid vaccination is required to attend in-person Charlotte Lit events. Send a picture of your vaccination card to staff@charlottelit.org. If you do not email it 24 hours before showtime, please be prepared to show proof of your vaccination at the door.

ABOUT IRANIA & BETH:

Irania Macias Patterson is an author and Certified Applied Poetry Therapy Facilitator (CAPF). For the past 22 years she has worked as an outreach program specialist for the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Her book Chipi Chipis, Small Shells of the Sea/Chipi Chipi Caracolitos del Mar, a winner of the 2006 International Reading Association Children’s Choice Award, Wings and Dreams: The Legend of Angel Falls. She also co-authored The Fragrance of Water, La Fragancia del Agua, and 27 Views of Charlotte. She is a 2020 recipient of an ASC grant assigned to write a poetry therapy play called Save the Tatas 2020. She holds a Master of Literature from La Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain, and a BA in Communication (UCAB) and Education (UNCC). She is also a trained teaching artist from Wolf Trap and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and a Road Scholar for the North Carolina Humanity Council. She is the co- founder of Criss Cross Mangosauce, an edutainment company for families.

Beth Murray, Ph.D., has been a public-school theatre teacher, a freelance teaching artist, a program development facilitator, and a playwright/author/deviser for young audiences across her career. Beth’s current trajectories of creative activity and research explore, describe, question, and foster spaces where young people and those who teach and reach them put theatre and all the arts to work for learning and intercultural understanding. The Mamá Goose Project, in which Beth was co-playwright and director of a multilingual play for young audiences as well as a professional development facilitator and principal investigator, exemplifies her collaborative, multi-disciplinary approach. Cotton & Collards: Unearthing Stories of Home through Kitchens & Closets is a current inquiry with local and global artists, educators, and the Levine Museum of the New South. Dr. Murray has published in academic and practitioner journals, such as Youth Theatre Journal, English Teaching Forum and Middle School Journal and has contributed to books and anthologies. She is the current Director of Publications for International Drama and Education Association (IDEA) and an Associate Professor of Theatre Education at UNC Charlotte.

Notebooking

Timothy: As a novice artist, I once spent several months drawing pictures of lizards and turtles for researchers in an animal behavior lab. I loved being around all the gadgets and learning the jargon of science, but the most interesting aspect was watching everyone fill up stacks of green notebooks with scribbled facts, figures, and thumbnail sketches. This largely unseen work of scientific exploration revealed to me a vastly bigger and more complex process than I’d imagined before.

Timothy: As a novice artist, I once spent several months drawing pictures of lizards and turtles for researchers in an animal behavior lab. I loved being around all the gadgets and learning the jargon of science, but the most interesting aspect was watching everyone fill up stacks of green notebooks with scribbled facts, figures, and thumbnail sketches. This largely unseen work of scientific exploration revealed to me a vastly bigger and more complex process than I’d imagined before.

Since then, my education as an artist has taken a pinball’s path, rolling and rocketing from bumper to flipper and back again. Now in the afternoon of this journey, after trying on a dozen different identities, I tell people (and myself) that I make books about books. But, ever skeptical of neat categories and descriptions, I wonder every day what this actually means.

It helps reaffirm my practice to think back to all those amazing lab notebooks overflowing with blue, black, and red ink. Their rich beauty, not meant for the eyes of the lay public, made me interested in the stories behind stories. Of course, I also have the privilege of living with a writer, who has filled so many shapes and sizes of notebooks with ideas. A finished book on the shelf or a painting on the wall can be wonderful things, but to me the messy, freewheeling preparatory work that flows though notebooks and sketchbooks is every bit as fascinating. So, I make, or at least try to make, book-like objects that talk about the often overlooked labor of art.

Bryn: And I have the privilege of living with a visual artist whose sketchbooks burst with wild, beautiful drawings and annotations. Our artistic disciplines intersect in the realm of notebooks: writers, artists, and other creative thinkers, as Timothy mentions, find these compact paper spaces crucial for process and discovery. Time and again, I’ve scratched bits of imagery, scenes, and characters during long walks or early morning coffee; later in the same pages, I’ve refined and expanded those bits or ditched them altogether. I’ve pasted encouraging quotes, pictures, and notes to self. When I drafted Sycamore, I first highlighted and tabbed pages in the stack of notebooks I’d been working in. Some of those scraps made it in wholesale.

Living with an artist, I also know how valuable it is to make a notebook for a project. Book artists in particular build mockups for their projects, mapping and testing structures, and then filling the pages with calculations and notes, before embarking on the final piece. Why shouldn’t writers, too, make their own project-specific notebooks? These serve not only to capture our ideas but to remind us from the start that this work should have its own personalized, playful space that also is practical and portable. Anyone can buy a readymade journal, but slowing down and constructing one from scratch is a kind of promise: This work matters. It’s in my hands now.

ABOUT THE INSTRUCTORS:

About the Instructors: Bryn Chancellor is the author of the novel Sycamore, a Southwest Book of the Year and Amazon Editors’ Best Book of 2017, and the story collection When Are You Coming Home?, winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, with work published in numerous literary journals. Honors include a 2018 North Carolina Arts Council Artist Fellowship and the Poets and Writers Maureen Egen Writers Exchange Award. She is associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Timothy Winkler is an illustrator and book artist whose Modern Fauna Art & Ephemera Studio is currently based in Charlotte. A native of Nashville, Tennessee, he has long studied and worked in all the various media of printmaking. He earned his MFA in Book Arts at the University of Alabama and has taught letterpress printing at Penland School of Crafts and a course on Outsider Art at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. Winkler was a 2020 recipient of an Arts and Science Council Artist Support Grant.

CREATE ZINES WITH BRYN & TIMOTHY: The road to a story winds through myriad notes and drafts. Join Bryn & Timothy on April 30, 2022 from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. for Little Notebooks, Big Ideas: Zines for Creative Exploration. Making notebooks by hand lets writers immerse themselves in the critical early creative process and helps them commit to a project. We’ll make fun, easy, affordable, and portable notebooks in the spirit of zines, closer to Anne Lamott’s index cards than to fussy bound journals. We’ll start to fill the pages with targeted prompts for characters, settings, and scenes, and play with simple printmaking and collage to make them our own. Register Here

Note: This class includes an hour break for lunch. You can bring your own or visit one of several walking-distance options.

My Creative Writing Journey Began at Charlotte Lit

After not touching a pen for years since high school, I showed up to Charlotte Lit in 2017 for my first creative writing class. I had taken a recent medical leave of absence from my job, and decided to start exploring forgotten creative longings, which after years of neglecting were starting to take a toll on my physical health and well-being.

After not touching a pen for years since high school, I showed up to Charlotte Lit in 2017 for my first creative writing class. I had taken a recent medical leave of absence from my job, and decided to start exploring forgotten creative longings, which after years of neglecting were starting to take a toll on my physical health and well-being.

I showed up with the desire to write, but had little understanding of writer’s craft or discipline. I immediately felt invited into the spaces and classes created by the co-founders, Kathie Collins and Paul Reali. I began with an interest in personal essay and memoir writing, then moved into discovering my love of poetry.

I met wonderful teachers like Kathie Collins, Dannye Romine Powell and Gilda Morina Syverson that immediately made me seen and valued. One of the first Charlotte Lit events that I attended was a 4x4CLT with poets Jessica Jacobs and Nickole Brown. I was drawn to their authentic voices and lyricism.

Through Charlotte Lit, I was also introduced to contemporary poets like Marie Howe, Mary Oliver. Ross Gay, Ada Limón and Terrance Hayes. Charlotte Lit helped me draw connections to poetry that I loved in my youth—Shakespeare, Dickinson and Keats—and see how contemporary poets incorporated craft elements like imagery, sound, rhythm and metaphor into modern language.

Charlotte Lit also led me to other personal artistic and creative endeavors. I began doing morning pages after hearing about the book The Artist Way which opened me up to exploring fashion and modeling, essentially the freedom to explore creative play.

Eventually, through the writing guidance and instruction that I received during my time at Charlotte Lit, I began to have some of my poems published. Now, I am currently working on my first chapbook through the Poetry Chapbook Lab.

I am grateful that I found a refuge in Charlotte Lit during a very difficult season of my life, which managed to help me during my own recovery and writing life. I found an entire community of people that are interested in similar ideas to me—poetry, mythology, beauty, mystery and the way language can help us describe the ineffable, both the joy and suffering in life.

Now, I am excited about coming aboard as Program Director to continue growing Charlotte Lit’s program offerings to the Charlotte community. I believe in the power of storytelling, and how literature brings us into conversations around belonging, empathy and personal/communal healing. I hope to infuse my passion for creative writing and strategic visioning by expanding the already vibrant list of Charlotte Lit’s programs to reach a growing and diverse audience of engaged writers and readers.

Below is one of the first poems that I had published, my first draft written during a poetry workshop that I took with Danny Romine Powell. The poem first appeared in Tipton Journal Issue 45.

Elegy for a Traveling Consultant

That year I worked in Philadelphia,

and I cried each time I packed my suitcase.

On the Mondays that ended early,

I strolled through Macy’s

sashaying through glittery shoes,

on ivory marble floors,

the Wanamaker Organ jolting

me from a phantom reel.

The evening recital became my respite

from a life that felt borrowed –

Walnut Street, Palomar Hotel,

mandatory happy hours,

snow falling in late March,

alone in my bedsheets.

Most days, I walked to the office,

except when rain showers soaked

the black and gold leather Tory flats

that a decade later, rest in my closet.

When summer arrived,

I ran through the city at night

like a breathless fugitive

down by the humid river

that made it feel hotter

than the South

where I longed to be back home.

Brooke Lehmann is Program Director at Charlotte Lit. She would love to hear your thoughts on our programming. Things you love? Things you’d like to see? You can reach her at brooke@charlottelit.org.