The Challenge is the Gift

By Beth Murray

Irania Macias Reymann and I are collaborators, kindred creative spirits, and we’ve written two plays together.

In 2013, we wrote and toured a bilingual show with music for children called Mamá Goose. It was inspired by the beautiful Latino nursery rhyme anthology of the same title by Isabel Campoy and Alma Flor Ada. In that project we challenged ourselves to make a play engaging and relevant to young audience members across language and cultural borders. We used music, movement, English, Spanish, American Sign language, playful actors, and all the design elements of theatre to tell the story for a diverse audience.

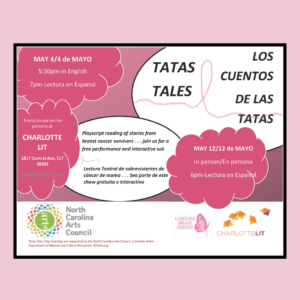

Our second play, Tatas Tales: Los Cuentos de las Tatas, is also an adaptation of sorts. We created the play based on the writing, conversations, drawings, stories, and community of breast cancer survivors participating in Irania’s bibliotherapy groups—some Spanish-speaking, some English-speaking. At this moment, we have an English and a Spanish version of the same play written to a point where actors can read the piece for an audience, and seek a response.

Despite the vast age and topic differences, both projects bear similarities. Both involve navigating cultural and linguistic borderlands with story. Both projects involve adapting existing material that is not in a single-narrative form. Both projects began with one of us saying something like: “There’s this thing. It has possibilities to be a play. I have no idea how right now. Will you collaborate with me?” We always say “Sí.” And then we see.

The challenges are the gifts. The weaknesses are the strengths. The doubts are the possibilities. The community matters more than we do. So, yeah. It takes us a long time to create a play. The plays become of a place and of the people who shape them along the way. For Tatas Tales, there have been many people and places.

Program administrators who held space for creative breast cancer therapies.

Bold and brave writing group members.

Readers and performers of early drafts on Zoom.

Community programmers and librarians willing to open their doors to our reading events. Media folks.

Current cast members.

Irania and I are named as playwrights, but Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas reflects a plurality of authors, as the story is continually written and re-written in rehearsal and performance choices by the ensemble, even as the words stay constant. Our current cast includes five actors.

Irania and I are named as playwrights, but Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas reflects a plurality of authors, as the story is continually written and re-written in rehearsal and performance choices by the ensemble, even as the words stay constant. Our current cast includes five actors.

The photo shows 12 people (a 13th in spirit). Among those smiling faces are professional performers, novice performers, breast cancer survivors, witnesses to breast cancer, monolingual English speakers, emergent Spanish speakers, bilingual speakers with varying degrees of comfort and confidence with English and Spanish, fluent multilingual speakers, young professionals, middle-career professionals, and retirees. This patchwork of people will bring the script to life. The initial challenge of not having five bilingual actors available for all performance gave way to this richness.

The challenge, again, became the gift. It is a generous one.

JOIN US for Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas:

JOIN US for Tatas Tales/Los Cuentos de las Tatas:

Wednesday, May 4: In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two, 5:30 p.m. in English – Register

Wednesday, May 4: In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two, 7:00 p.m. in Spanish – Registro

Thursday, May 12: Hybrid event, 6:00 p.m. in Spanish

• In-person in Charlotte Lit’s Studio Two – Registro

• Virtual through Charlotte Mecklenburg Library – Registro

NOTE: Proof of full Covid vaccination is required to attend in-person Charlotte Lit events. Send a picture of your vaccination card to staff@charlottelit.org. If you do not email it 24 hours before showtime, please be prepared to show proof of your vaccination at the door.

ABOUT IRANIA & BETH:

Irania Macias Patterson is an author and Certified Applied Poetry Therapy Facilitator (CAPF). For the past 22 years she has worked as an outreach program specialist for the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Her book Chipi Chipis, Small Shells of the Sea/Chipi Chipi Caracolitos del Mar, a winner of the 2006 International Reading Association Children’s Choice Award, Wings and Dreams: The Legend of Angel Falls. She also co-authored The Fragrance of Water, La Fragancia del Agua, and 27 Views of Charlotte. She is a 2020 recipient of an ASC grant assigned to write a poetry therapy play called Save the Tatas 2020. She holds a Master of Literature from La Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain, and a BA in Communication (UCAB) and Education (UNCC). She is also a trained teaching artist from Wolf Trap and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and a Road Scholar for the North Carolina Humanity Council. She is the co- founder of Criss Cross Mangosauce, an edutainment company for families.

Beth Murray, Ph.D., has been a public-school theatre teacher, a freelance teaching artist, a program development facilitator, and a playwright/author/deviser for young audiences across her career. Beth’s current trajectories of creative activity and research explore, describe, question, and foster spaces where young people and those who teach and reach them put theatre and all the arts to work for learning and intercultural understanding. The Mamá Goose Project, in which Beth was co-playwright and director of a multilingual play for young audiences as well as a professional development facilitator and principal investigator, exemplifies her collaborative, multi-disciplinary approach. Cotton & Collards: Unearthing Stories of Home through Kitchens & Closets is a current inquiry with local and global artists, educators, and the Levine Museum of the New South. Dr. Murray has published in academic and practitioner journals, such as Youth Theatre Journal, English Teaching Forum and Middle School Journal and has contributed to books and anthologies. She is the current Director of Publications for International Drama and Education Association (IDEA) and an Associate Professor of Theatre Education at UNC Charlotte.