Mark West Reflects on 40 Years of Community Engagement in Charlotte

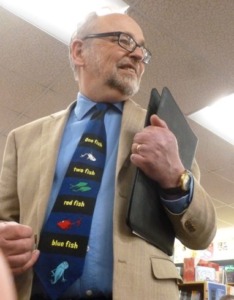

Mark West

When we heard that Mark West was celebrating 80 semesters teaching at UNC Charlotte, we knew we had to do something to commemorate the occasion.

Mark has been a tremendous supporter of Charlotte Lit, most notably through his fantastic blog Storied Charlotte, which has become an integral part of our community’s literary landscape. It’s almost as if it hasn’t happened until Mark has written about it, which makes our many appearances there particularly gratifying for an org currently in just our 16th semester.

As turnabout is fair play, we decided to take a page (pun intended) from Mark’s blog playbook and ask him to tell his story. Here’s what he wrote to us:

I began my career as an English professor at UNC Charlotte in 1984. As I reflect on my forty-year career, I cannot remember a time during which I was not deeply involved in community engagement work. For me, my work as an English professor and my commitment to community engagement go hand in hand. Whether I am teaching a course on children’s literature, volunteering at a public library event, or participating in a community forum about resisting censorship pressures, I am always doing what I can to encourage people to read and appreciate literary works. As I see it, a literary work does not really blossom into literature until it has readers. A book without readers is like an unplanted seed—full of potential but needing a little space and attention in order to take root in the imagination of a reader.

My Storied Charlotte blog is a direct outgrowth of my community engagement work. I launched my blog four years ago in an effort to draw attention to Charlotte’s vibrant literary community. This community includes more than writers. It also encompasses librarians, booksellers, publishers, literacy activists, writing groups and organizations, and (most importantly) readers.

My blog has much in common with Charlotte Lit. Both are rooted in Charlotte’s community of readers and writers, and both celebrate authors from Charlotte. Not surprisingly, I have written many Storied Charlotte blog posts about Charlotte Lit’s activities and projects over the past four years. Although there is no formal connection between my Storied Charlotte blog and Charlotte Lit, our shared purpose makes us partners.

We feel the same way, Mark. Partners we are. Thanks for everything you do for Charlotte’s storied literary community.

The Magic of Listening to Stories

by Meghan Modafferi

If you tune into NPR, sooner or later you’ll hear the phrase “driveway moment.” It’s when you’ve reached your destination, but you just can’t bring yourself to turn off the radio, to get out of the car. You have to hear the ending of the story that’s airing on, say, This American Life.

If you tune into NPR, sooner or later you’ll hear the phrase “driveway moment.” It’s when you’ve reached your destination, but you just can’t bring yourself to turn off the radio, to get out of the car. You have to hear the ending of the story that’s airing on, say, This American Life.

Ever wonder how the writer did that? When attention spans are shorter than ever, how do you keep someone hooked when you have access to only one of their senses—hearing?

Like anything in writing, or life, there are millions of answers to every question. But for me, I keep coming back to the essay. Or, rather, the essai; in French, the meaning is “to attempt.” It describes an intimate perspective, with a narrator who’s searching rather than concluding. While traditional nonfiction delivers the results of a study or investigation, literary essays focus on the journey—as interior as it is exterior, full of wrong turns and dead ends, where doubts and emotions are not detours to avoid but the very meat of the story. Where how the sausage gets made and the sausage itself start to blur. Where the narrator shows themself in the attempt to understand rather than already understanding.

If you’ve listened to The New Yorker Radio Hour or watched a video essay on YouTube, you’ve likely heard this approach. It’s powerful to the ear because of its intimacy. Think about it: we all live in a state of searching. We don’t live in neat, cohesive stories; we live in a muddle that we make sense of until something breaks that sense, and then we have to find a new angle to make sense of it again.

And when someone speaks directly into your ear and tells you about that journey in their own mind, it’s electric, like a magician sharing their secrets. Because what’s more magical than taking the mess of life and making it into a story? It’s what we spend all our time doing—as writers, yes, but also as humans. Joan Didion wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

So when, inevitably, the narrator in your ear doesn’t find what they were looking for but something else that’s even richer and more meaningful, it gives us hope. Hope that we, too, are on a journey of discovery that only gets sweeter with each wrong turn. And with that kind of magic, you simply can’t help it: you put the car in park and keep listening.

Learn to Write and Record a 3-Minute Essay with Meghan

THREE THURSDAYS, FEBRUARY 8, 15, & 22: “The Sound of Writing: Writing and Recording the 3-Minute Essay,” 6:00-8:00 p.m., Charlotte Art League, 4237 Raleigh Street, Charlotte 28213. Info and registration

In this three-session course, you’ll learn what makes a great spoken essay; draft, get feedback, and edit an essay; learn the basics of being recorded; and record your three-minute essay in a professional sound studio.

Meghan Modafferi is the editorial director of Crash Course, an award-winning YouTube channel reaching more than 70 million people per year. She has taught writing and podcasting at Georgetown University, and her written and multimedia work has been published by National Geographic, Slate, and NPR.

Origins of a Poem

by Chen Chen

This poem started out as a tweet that was a bit more lyrical than usual. One of my favorite joys: when poems come from unexpected, seemingly unpoetic places.

I Love You to the Moon &

not back, let’s not come back, let’s go by the speed of

queer zest & stay up

there & get ourselves a little

moon cottage (so pretty), then start a moon garden

with lots of moon veggies (so healthy), i mean

i was already moonlighting

as an online moonologist

most weekends, so this is the immensely

logical next step, are you

packing your bags yet, don’t forget your

sailor moon jean jacket, let’s wear

our sailor moon jean jackets while twirling in that lighter,

queerer moon gravity, let’s love each other

(so good) on the moon, let’s love

the moon

on the moon

Copyright 2021 by Chen Chen. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on May 31, 2021, then reprinted in Explodingly Yours (Ghost City Press, 2023). Reprinted with permission of author.

Learn to Write Poems Celebrating Connection and Love: A Masterclass with Chen Chen

TUESDAY, JANUARY 23: “Happy Poems!” 6:00-8:00 p.m. via Zoom.

Do happy poems exist? If they do, can they be as good as the poems that wreck us? Can a happy poem wreck us? And how can we avoid sentimentality or, is that a risk we just need to take? In this generative session, we’ll look at Ross Gay’s essay, “Joy Is Such a Human Madness” as a compass for our discussion and a starting point for writing about/from/through happiness, joy, and pleasure. Within the genre of happy poems, we’ll think about poems that celebrate love, sex, community, and connection of various kinds. Come prepared to engage in jubilant experimentation. Info and registration

About Chen

Chen Chen is the author of two books of poetry, Your Emergency Contact Has Experienced an Emergency (BOA Editions, 2022) and When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities (BOA Editions, 2017), which was longlisted for the National Book Award and won the Thom Gunn Award. His work appears in many publications, including Poetry and three editions of The Best American Poetry. He was the 2018-22 Jacob Ziskind Poet-in-Residence at Brandeis University and currently teaches for the low-residency M.F.A. programs at New England College and Stonecoast. Visit his website: chenchenwrites.com

What IS an Essay?

By Randon Billings Noble

By Randon Billings Noble

What is an essay? A basic five-paragraph argument? A long and rambling meditation? A deep dive into academic research? A funny or embarrassing personal anecdote?

Yes … but also no. An essay can be so much more than we might first think.

Montaigne is known as the father of the essay. Reading him now can feel like heavy sledding. His 16th-century prose is ornate and demands a level of attention our 21st-century minds aren’t used to, but what he was writing was revolutionary. After retiring from politics, he decided to write about himself, his thoughts, his experiences, his realizations. Before this, most first-person writing was confessional in the religious sense. But Montaigne wrote about more earthly concerns, like friendship, sadness, idleness, letter-writing, sleep, death, clothes. He used his own experiences to discover intellectual insights. He created – or at least radically shaped – a new form of writing.

When pressed for a brass-tacks definition of an essay, I use one I learned in graduate school: an essay is a piece of writing with a beginning, middle, and end that develops an idea in an interesting way. Note that an essay doesn’t require an introduction, body, and conclusion; it doesn’t have to end so neatly. Nor does it a require a thesis; essays can do more than argue or prove. An essay can question, wonder, warn, dismantle, challenge, gesture to, forecast, probe, propose, or explore.

Annie Dillard writes that the “essay is, and has been, all over the map. There’s nothing you cannot do with it; no subject matter is forbidden, no structure is proscribed. You get to make up your own structure every time, a structure that arises from the materials and best contains them.”

Look at Adam Gopnik’s somewhat traditional essay “Bumping into Mr. Ravioli,” which starts with a story about his daughter’s imaginary friend but then expands to do some serious thinking about the ways our tech-filled urban lives keep us too busy for real connection. Or look at Sarah Einstein’s segmented essay “A Young Man Tells Me,” which uses a list to comment on contemporary masculinity without ever making an overt (or thesis-y) claim about it. Or look at Christine Byl’s flash essay “Bear Fragments,” which is exactly what it sounds like: seven short fragments about bears. What do they add up to? That’s up to the reader to decide.

The core of an essay is an idea, something that the writer thinks, something they want to say. But the way to say it is nearly boundless. Each essay’s structure is unique to the ideas within. Funny, thoughtful, subtle, sharp, meditative, pointed, meandering – there’s much more to the essay than five paragraphs.

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her collection Be with Me Always was published by the University of Nebraska Press in 2019 and her anthology of lyric essays, A Harp in the Stars, was published by Nebraska in 2021. Other work has appeared in the Modern Love column of The New York Times, The Rumpus, Brevity, and Creative Nonfiction. Currently she is the founding editor of the online literary magazine After the Art and teaches in West Virginia Wesleyan’s Low-Residency MFA Program and Goucher’s MFA in Nonfiction Program. You can read more at her website, randonbillingsnoble.com.

Learn to Write Segmented Essays with Randon. Randon Billings Noble leads “Segmented Essays: When the Whole is Greater than the Sum of Its Parts” for Charlotte Lit via Zoom, Tuesday, December 5, 2023, 6:00-8:00 p.m. Info and registration

Mindfulness & Poetry

by Brooke Lehmann

In my meditation circle a few weeks ago, our group leader asked us to name one of our wisdom teachers. The contemporary poet and Zen Buddhist Jane Hirshfield came to mind; I was currently reading her new collection, The Asking. Hirshfield’s poems are filled with ordinary acts such as picking figs or opening a window. Many of her poems grapple with difficult questions: the climate crisis, aging, and human suffering. They often instill a sense of wonder and gratitude alongside grief and loss.

In my meditation circle a few weeks ago, our group leader asked us to name one of our wisdom teachers. The contemporary poet and Zen Buddhist Jane Hirshfield came to mind; I was currently reading her new collection, The Asking. Hirshfield’s poems are filled with ordinary acts such as picking figs or opening a window. Many of her poems grapple with difficult questions: the climate crisis, aging, and human suffering. They often instill a sense of wonder and gratitude alongside grief and loss.

In the early days of reading poetry, I was drawn to the imagery and music of the language. But over the years, I have realized that the poems I love the most are not just filled with writing craft, but they also teach me the most about how to live well or more mindfully. Hirshfield says, “Through poetry I know something new, and I have been changed.”

Mindfulness is living in the present moment, accepting our thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations without judgment. Mindfulness is a quality everyone possesses, but we must learn how to access it. Like any new routine or habit, the more we practice, the easier it becomes over time. We can exercise mindfulness in everyday activities like walking, cooking, folding laundry, or reading a poem.

Research suggests a regular mindfulness practice reduces stress, improves mood and focus, strengthens our immune system, and stimulates learning and creativity. Mindfulness can also help us have happier relationships, make us more resilient to suffering, and allow us to cultivate compassion for ourselves and others. Similar to practicing yoga, we can feel kinder towards ourselves and others by reading mindfully.

We see poets like Craig Arnold, with his poem, “Meditation on a Grapefruit,” slow his readers down to the simple act of savoring a piece of fruit over breakfast before the day’s stressors set in. In the poem “Thank You” by Ross Gay, readers are placed barefoot on the frosty grass of a dormant garden in early fall. Through enlivening the senses, we are gifted with greater clarity in the present time. It’s one thing to be on a meditation retreat away from distractions, but by reading, we can learn to witness mindfulness in moments of daily living.

As we live in increasing uncertainty in our ever-changing world, I routinely turn to poetry to ground me in the present moment. Against the terror and dread that we face with gun violence or threats of war, reading mindfully helps me see the beauty alongside the pain in others’ experiences. It reminds me of possibilities that exist in what I often tend to overlook. Right now, the invitation to open to the dark drop of autumn and watch nature surrender to its own wisdom.

About Brooke: Brooke Lehmann is a poet and creative who draws inspiration from nature, fashion, and her love of the piano. Her poems have been featured in Tar River Poetry, Pedestal Magazine and others. She was longlisted for the 2022 Palette Poetry Sappho Prize for Women Poets, and her chapbook manuscript, Pillar of Exquisite Sorrows, was named a finalist in Tusculum Review’s 2023 Chapbook Prize. Brooke holds a B.S. from Purdue University and is a graduate of the Arts and Science Council Cultural Leadership Training program. She serves as an advisory group member of Charlotte Center for Mindfulness.

Practice Mindfulness with Brooke: “The Poetry of Presence: Reading as a Path to Mindfulness,” Thursday, November 9, 2023, 6:00-8:00 p.m., virtual via Zoom.

In this class we’ll explore a few poems and short pieces around the theme of mindfulness. Class will open with a guided body scan meditation followed by a series of readings that follow the style of lectio divina or dharma contemplations. We’ll respond to how the essence of the poems take shape in an embodied way as we hear them recited, informing our emotional and inner landscapes. As a group we’ll discuss images or phrases that catch our attention, and the way metaphor creates meaning and resonance in our lives. We will also have time for a mindful writing exercise and optional sharing. Info

Celebrate the Writer You Are AND the Writer You Can Become

By Ashley Memory

While no one likes to get a rejection email, I recently received one that wasn’t quite as bad as most. It read: “Unfortunately, your submission is not the right fit for what we’re seeking at the moment, but please know that your story is valid and important. We would love to see your work again Ashley!”

I realize that this message was a form letter, and even the name field was auto-populated, but it had a curious effect on me. This note not only softened the blow, it also made me feel better about my writing. It reinforced my belief that all writers instinctually pull from a collective consciousness of love, sadness, grief, joy, and everything in between. This does indeed make my work, and your work, both valid and important.

From one writer to another, I urge you to take this opportunity to love yourself and your work. As often as writing exhilarates, liberates, and soothes, it equally infuriates, bewilders and exhausts us. That’s why it’s so important to give yourself permission to write and believe in your work.

To help, I’ve provided six quick steps designed to celebrate both the writer you are and the writer you can become.

1) Remember the time when you first knew that you were a writer. This happened for me in the sixth grade, when I wrote a poem on the first Thanksgiving that my teacher Mrs. Robbins posted outside the classroom. My first “masterpiece” was a little corny, and certainly contained predictable rhymes, but it meant so much that a teacher I admired was proud of me. I want to do this for the rest of my life, I remember thinking. This little victory has sustained and lifted me up ever since.

2) Tell people that you’re a writer. This step is so obvious I almost didn’t include it. But in my career, I’ve met so many people (even at writers’ conferences!) who hesitate to call themselves writers. They scribble under the cover of darkness, never share their work, and don’t trust themselves enough to tell the world about their greatest, albeit secret, passion. It’s time to come clean. “Outing” yourself as a writer will bolster your confidence and open a new world of friends and connections.

3) Celebrate your strengths. Marilyn, a dear writing partner, recently asked me to compile a list of her greatest writing strengths, something that I was delighted to do. She plans to use this list as part of her 2023 writing plan, which in my mind is nothing short of brilliant. You should do the same. Ask someone in your life—either a fellow writer or a reader of your work—what they admire most about your writing. Keep this list handy and refer to it often.

4) Love your writing enough to make it better. While it’s important to celebrate our talents and victories, it’s vital that we look beyond those moments and seek to improve. If you’re naturally good at setting a scene, consider pushing yourself to add more conflict. If characterization is your strong suit, tinker with your descriptions a little more. Or get better at finding just the right word to express yourself. One of my Christmas presents was the game “Wordsmithery” and by playing it, I hope my writing will soon be much more incandescent.

5) Post self-affirmations where you can see them. I’m living my best writing life. I move people with words. I will write a new poem every week. I will achieve my writing goals this year. You can post these by your writing desk or on your computer screen, but you can also stick them up throughout your home. Because we writers know that some of our best writing happens in our head—when we’re not actively writing. For example, I like to post my notes over the cooktop, on my nightstand, and even in the mirror. Collect your own affirmations, read them out loud, and repeat often.

6) Challenge yourself by submitting to a more competitive market. What is your dream publication? Have you been putting off submitting out of fear? Doubt? Procrastination? Don’t automatically assume that you’ll get a “no.” Just the act of considering ourselves worthy of our most aspirational markets is an elixir to the psyche. Start submitting to more selective markets and I promise that you will begin to see yourself and your work in a new light.

And on this note, why not start NOW? That’s right. Step out of your comfort zone and submit your work to an editor who might be waiting just to hear from you.

Writing as Triathlon

When I first began writing, I believed the most difficult part would be finishing a full-length manuscript, so I only thought it was important to take classes relating to story craft. It was a rude awakening to realize there was so much more I needed to know if anyone was ever going to be able to buy my book and read it.

When I first began writing, I believed the most difficult part would be finishing a full-length manuscript, so I only thought it was important to take classes relating to story craft. It was a rude awakening to realize there was so much more I needed to know if anyone was ever going to be able to buy my book and read it.

In a 2002 NY Times article, Think You Have a Book in You? Think Again, author Joseph Epstein cited a study that revealed “81% of Americans feel they have a book in them.” He goes on to use the rest of his essay to dissuade people from writing and suggests instead, “Keep it inside you where it belongs.”

Apparently, a lot of people do as Epstein suggests and “save the typing, save the trees.” On Reedsy.com, a blog states .01% ever make it to their goal of finishing that book. No doubt that is because a crafting great story is only about 30% of the book problem. Once authors type “The End,” it’s only the beginning of a long process to write query letters, secure an agent, sign a book contract and market the book. Add on to that the frustrating demand from publishers that writers must also build a “platform” on social media to sell their work, and really, it does seem like Epstein might have been right.

At the same time, it has never been easier for authors to bypass the agents who are gatekeepers of the Big Five publishing world and create their own books. The idea of “self-publishing” is not new, dating back to 1439 when the first printing press was invented by a German goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg. Fast forward to 1979, when computers made desktop publishing accessible and the current print-on-demand technology possible.

In the last forty years, Amazon (KDP Direct) and Ingram (IngramSpark) have dominated and consolidated the POD world, creating a level of sophistication that can make a self-published book indistinguishable from traditionally published titles. But to navigate this part of the publishing universe, aspiring writers must learn how to turn their manuscripts into properly formatted files—a process which can seem daunting.

In truth, it simply takes more of the same persistence required to finish your 65,000-word manuscript. You can learn how to master plot lines and dialogue, as well as how to publish your own great book. Take, for example, the determination of Lisa Genova.

In 2007, she was simply a grad student who had received multiple rejections from traditional publishers. But Genova believed in her manuscript based on the story of her grandmother’s early onset Alzheimer’s, so the aspiring author self-published. After gaining popularity with readers, Simon & Shuster picked up the title and republished it two years later under the title Still Alice. Genova’s book, which had been initially rejected, was on The New York Times Best Seller List for more than 40 weeks, sold in 30 countries, translated into 20 languages, and became an Oscar-winning film. None of that would have happened if Genova had not taken the initiative to publish her own book.

In reality, writing a book is like completing a triathlon—and each of the three stages takes training: writing, publishing and marketing. Don’t wait until your last page to think about how to get your book in the world. Start now, learning to navigate the publishing and book-marketing world.

Maybe even more important than crafting your great characters is learning how your readers will ultimately discover them.

Learn About Self-publishing with Kathy

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2023: “Paths to Self-Publishing,” 6:00-8:00 p.m., in-person at Charlotte Lit

So, you’ve finished a manuscript and have made the decision to self-publish. Where do you start? Or, maybe you worry that self-publishing means “settling” for an unprofessional product. No matter on which side of that fence you sit, the volume of information and opinions is overwhelming. It can be difficult to know which services to trust and whether self-publishing is right for you. Kathy Izard has published four books three ways, including self-published and “Big Five.” Kathy will walk you through 10 steps to putting your words in the world. From purchasing your own ISBN number to ordering author copies, Kathy can answer all your questions about becoming a published author of adult or children’s books. Info

About Kathy

Kathy Izard is an award-winning author and speaker who writes inspirational nonfiction, including The Hundred Story Home, The Last Ordinary Hour and her upcoming release Trust the Whisper (Summer 2024). Kathy also publishes children’s books including A Good Night for Mr. Coleman and Grace Heard a Whisper (Fall 2023). Kathy has written essays for Katie Couric Media and her work as been featured on the Today Show, inspiring people to be changemakers in their community. Online: kathyizard.com.

All Details are Not Created Equally

by Craig Buchner

I have a vivd memory from graduate school at Western Carolina, almost 20 years ago. My thesis director commented on my final project, a collection of a few short stories. He said that the details I chose in those stories were particularly precise and thoughtful. At that time in my writing development, I was including details that quickly came to mind, and I would settle on one or maybe two details within a scene to highlight—choosing efficiency of language over any greater world building. At the time, it was easier to write in a more clipped, Hemingway-style, and it saved time so I could focus more energy on developing the narrative and plot.

I have a vivd memory from graduate school at Western Carolina, almost 20 years ago. My thesis director commented on my final project, a collection of a few short stories. He said that the details I chose in those stories were particularly precise and thoughtful. At that time in my writing development, I was including details that quickly came to mind, and I would settle on one or maybe two details within a scene to highlight—choosing efficiency of language over any greater world building. At the time, it was easier to write in a more clipped, Hemingway-style, and it saved time so I could focus more energy on developing the narrative and plot.

Two decades on—after publishing two books—I still write like this, but it isn’t for the same reasons. Instead, I realize that a focused detail or two can add a deeper layer or dimension to a story.

For example, in my collection of short stories Brutal Beasts I include a story called “Held in Place by Teeth that Face Inward,” in which the protagonist goes to a dive bar with his brother after said brother is arrested. While the brother orders “two Mich Lights and two shots of Fireball,” the protagonist settles on a Sprite “with a slice of lime if you got it.” This drink choice allows me, the author, to establish that the protagonist is sober and moreover that he carries a backstory far more nuanced than the present story at hand. The protagonist makes choices in the scene based on a history he carries, yet that history never has to be explicitly told.

For me, this example illustrates that a well chosen, intentional detail can carry a significant amount of weight within a story that, if positioned well, can establish tension within a scene and between characters, and it supersedes unnecessary backstory or a lengthly explanation, which might slow down the story too much. Too many specific details, in this view, can dilute a scene, leaving a reader to wonder where they should focus their attention, and ultimately lose sight of a key detail that might come back later in the story to reinforce a climactic moment.

I’ve always been attracted to brevity in stories, but it’s taken me a couple decades to understand the true power of it within storytelling. So, I leave you with this thought: Details matter, but not all of them. Choose wisely!

Learn Short Story Writing with Craig

BEGINNING NEXT TUESDAY: “Writing the Short Story,” three Tuesdays, September 26, October 3 & 10, 6:00-8:00 p.m., virtual via Zoom.

“Cut the piano in half with a chainsaw.” How can this advice influence us to write the best short stories? In this three-week course, we’ll learn how to write a captivating scene for a short story, and explore what a successful scene should accomplish. We will also break down the essential elements of a short story, including character, setting, and dialogue. In lieu of workshopping, writing exercises will give students opportunities to apply these lessons to their own work. And what about that “piano”? We’ll hear that story in the first class!. Info

About Craig

Craig Buchner holds an M.F.A. from the University of Idaho and a M.A. in English from Western Carolina University. He’s taught writing at Brevard College, Washington State University, and Portland Community College. His debut collection of short stories, Brutal Beasts (NFB Publishing), was chosen as an “Indie Book of the Year” in 2022 by Kirkus Reviews. He is also the author of the novel Fish Cough (Buckman Press), which was named an “Indie Books We Love” by LoveReading in 2023. Craig lives with his family in Charlotte.