Poetry, Wellness, and “The Slowdown”

Because I am a writer, my attention can become very centered on craft. I also teach. One afternoon, my creative writing students at Queens University pointed out that I’d failed to remark on the fact that all the poetry examples for the day were about death—I’d been too intent on exploring how the figurative language functioned. They surely had a point. As Lucille Clifton said, “Poetry is a matter of life, not just a matter of language.”

Poems ask us to stop and think. We reread a poem to unpack the compressed power of its metaphor, diction, and arrangement. Appreciating this fully warrants focus—something a healthy mind requires. After a period of intense focus, I know I feel better. Time seems to both stop and to impossibly extend itself. By objective measure, more time has actually passed than it seems. I look up and wonder: Was that really two hours?

What makes me feel less well? The pull of my attention onto too many interrupting and competing tasks, considerations both important and frivolous, near and far, swirling together and visually vying for my attention to screens. These days I sometimes find myself working on multiple undertakings simultaneously, and less successfully, without fully realizing that I’m jumping from one to another. (How did this happen to my brain?)

Poetry is the perfect antidote for today’s particular malady. According to the National Endowment for the Arts, poetry readership is on the rise. Now that I’m looking, the connection between poetry and health seems to be everywhere. William Sieghart recently ran a poetry pharmacy for which he prescribed particular verses for readers’ problems (this is now a book). The Paris Review has a similar project, a blog column Poetry Rx. And like literary fiction, poetry is sure to improve empathy. Poet Linda Gregerson has reflected on how it can help repair the damage evident in our current civic discourse.

In her latest project, Tracy K. Smith, the nation’s poet laureate and April 2018’s 4X4CLT featured poet, centers on the personal, daily value that poetry provides. If you aren’t already, become a fan of her podcast The Slowdown, produced in partnership with the Library of Congress and the Poetry Foundation. Every weekday, she offers an episode detailing how a poem matters to her personally, what it makes her feel and remember, or how she reacts to its music.

Then she reads the poem in her practiced, calm voice. This tends to be my favorite part of the experience. Five minutes is all you need. “Life is fast, intense and sometimes bewildering,” explains Smith in the introduction to the series. “But poetry offers a way of slowing things down, looking at them closely, mining each moment for all that it houses.” She argues for the necessity of “living more deeply with reality” through poetry. She models for listeners how a poem engages her. Poems express what is relatable yet has felt beyond expression. Poems can be a call to action, connecting us to family and to society. They can also just be a pleasure to say out loud, and whatever they might mean can be beside the point.

In The Slowdown, you’ll find another Charlotte Lit connection, June 2018’s 4X4CLT featured poet, Tyree Daye, Episode 60, Tamed. You’ll find Queens University MFA faculty member Ada Limón, Episode 27, The Raincoat. You’ll find older poetry too, such as Emily Dickinson, 64: I like to see it lap the Miles. What resonates most deeply for you will be for reasons of your own. For example, for me, Episode 48, Elegy for Smoking by Patrick Phillips resonates not because I was ever a smoker, I wasn’t. But in the 1990s, I boldly asserted my right to what I called a smokeless smoke break. I would follow the addicts (including my boss, someone I miss) out to the patio and take a work-break too. Who would have argued with who I was back then, both earnest and mouthy, asserting my right to stare at the trees for the length of time a cigarette would require? Smith has her own way of connecting to the poem. Connecting is absolutely the point.

A few spaces remain for Julie Funderburk’s workshop “A Poem That Sings” on Saturday March 16 from 10 am to 1 pm. Register here.

Julie Funderburk is author of the poetry collection The Door That Always Opens from LSU Press and a limited-edition chapbook from Unicorn Press. She is the recipient of fellowships from the North Carolina Arts Council and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and a scholarship from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Her work appears in Best New Poets, Cave Wall, The Cincinnati Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and Ploughshares. She is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Queens University in Charlotte, where she directs The Arts at Queens.

Featured links:

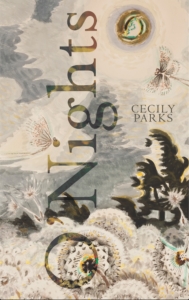

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic, hermited study of the natural world, he acknowledges his immersive contemplation might be considered odd. “This was sheer idleness to my fellow townsmen, no doubt; but if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should not have been found wanting.” That standard—of the stars, the moon, the meadow—is the one Cecily Parks’ aspires to in her second collection of poetry, O’Nights (Alice James Books, 2015). Its speaker is the female incarnation of a present-day wanderer trying to commune with what’s left of the wild, one whose solitary forest wanderings mark her even after she finds love and returns to an urban environment.

In Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s classic, hermited study of the natural world, he acknowledges his immersive contemplation might be considered odd. “This was sheer idleness to my fellow townsmen, no doubt; but if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should not have been found wanting.” That standard—of the stars, the moon, the meadow—is the one Cecily Parks’ aspires to in her second collection of poetry, O’Nights (Alice James Books, 2015). Its speaker is the female incarnation of a present-day wanderer trying to commune with what’s left of the wild, one whose solitary forest wanderings mark her even after she finds love and returns to an urban environment. O’Nights, which takes its title from an anecdote found in Thoreau’s journal, is split into three sections. In the first, the speaker is alone and spends her days (and nights) closely observing the natural world. While she may be the sole human, her solitude expands to encompass a wider community of the forest where she finds herself in conversation with the wild entities that surround her. She is alone, but not lonely. “Hurricane Song,” the powerful, opening poem, describes the “little kidnapped thrill that comes with drastic weather,” the feeling of being out in a storm’s overture. She’s on the same level as the pines, the grass, and the deer who “flips herself over and over, white tail-spark,/black hoof-sparks, brown wheel.” This leveling serves as a reminder that we humans are animals after all, still part of an ecosystem, still subject to the whims of weather. A sense of restless energy runs through this section as the speaker, eschewing comfort and convention, roams alone.

O’Nights, which takes its title from an anecdote found in Thoreau’s journal, is split into three sections. In the first, the speaker is alone and spends her days (and nights) closely observing the natural world. While she may be the sole human, her solitude expands to encompass a wider community of the forest where she finds herself in conversation with the wild entities that surround her. She is alone, but not lonely. “Hurricane Song,” the powerful, opening poem, describes the “little kidnapped thrill that comes with drastic weather,” the feeling of being out in a storm’s overture. She’s on the same level as the pines, the grass, and the deer who “flips herself over and over, white tail-spark,/black hoof-sparks, brown wheel.” This leveling serves as a reminder that we humans are animals after all, still part of an ecosystem, still subject to the whims of weather. A sense of restless energy runs through this section as the speaker, eschewing comfort and convention, roams alone.